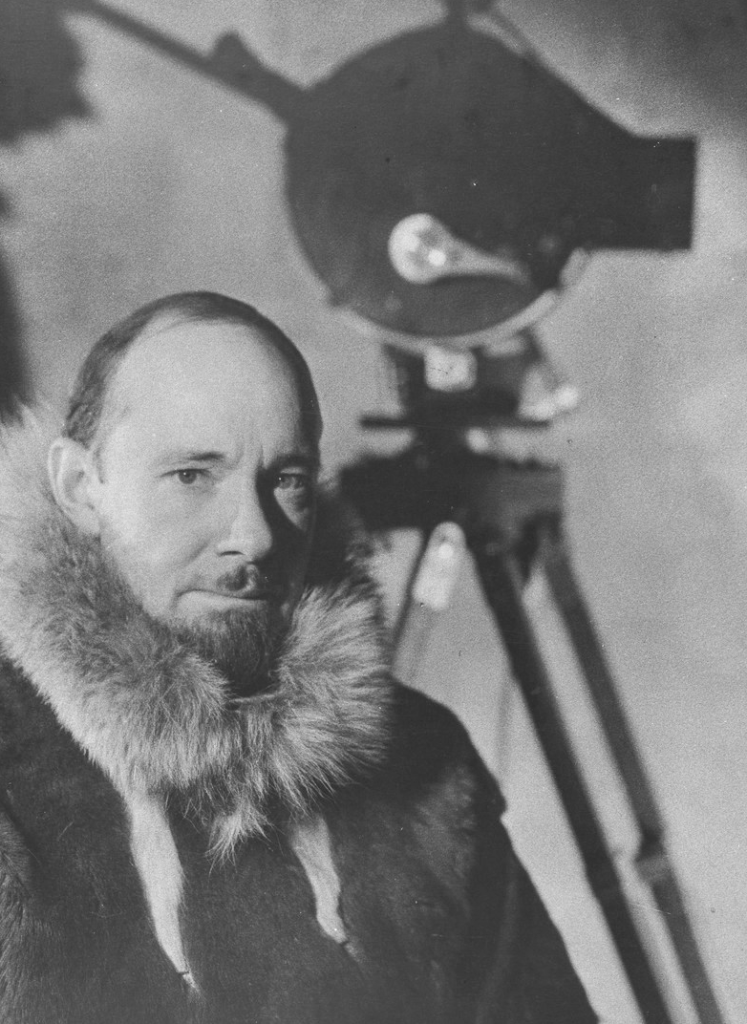

Sir George Hubert Wilkins is one of the most famous people you’ve never heard of. In April of 1928, he was a global household name, on par with Charles Lindbergh, receiving a ticker tape parade in New York City for piloting the first successful Trans-Arctic flight from Point Barrow, Alaska to Spitsbergen, Norway. For some men, that would be sufficient for one lifetime, but Hubert Wilkins was one of the most extraordinary men of any age. He would spend two years traversing Northern Australia on foot for the British Museum, serve as Shackleton’s biologist, make the first attempt to travel under the Arctic by submarine and is generally considered one of the greatest explorers in human history.

What does this have to do with cinema? It was filmmaking that gave Hubert Wilkins his entry point to a life of adventure and innovation. Born and raised in a dusty corner of South Australia, he was introduced to film at the turn of the 20th century by an itinerant motion picture outfit, and after stowing away to London by way of Algiers, was hired by the Gaumont Company as a cinematographer. In 1910, he would learn to fly with Claude Grahame-White and Gaumont would soon send Wilkins to Turkey to film the Balkan War. There he would become not only the first person to film on the front line of a war, but he would pioneer aerial photography as well, utilizing both hot-air balloons and bi-planes to capture images of the conflict. He was captured by the Bulgarians and somehow avoided being executed. In 1917, he would return to the front lines of World War I with the Australian Army as an war photographer, becoming the only person in that role to earn the distinguished Military Cross for rescuing wounded soldiers unarmed at the Third Battle of Ypres.

His filmmaking career would continue after the war with the Quakers hiring him to cross Russia making four films collectively called New Worlds for Old about the influenza epidemic and famine gripping the new communist nation. He would be nearly eaten by Russians driven to cannibalism by severe starvation. When he finished his filming, he would become one of the last Westerners to meet with Lenin before the communist leader died.

Wilkins would focus primarily on exploration as his career progressed after the 1920s. Amazingly, none of daring exploits would cause his demise. Wilkins would pass away in 1958 from a heart attack at age 70 while working on his car.

Our cocktail for this installment is a nod to the fact that Wilkins and his wife were part of the first aerial circumnavigation of the planet aboard the Graf Zeppelin’s ‘Round-the-World’ voyage in 1929. Several years later in 1936 when the Zeppelin Hindenburg made its maiden journey to the United States from Frankfurt, the bar would run out of gin over the Atlantic. One of the passengers, Pauline Charteris (the wife of “The Saint” Simon Templar creator Leslie Charteris) fashioned a replacement martini with the on-board stores of German cherry brandy, kirschwasser.

Pauline Charteris’ Hindenburg Cocktail

- 3 oz kirschwasser

- 1/2 oz dry vermouth

- A splash of Grenadine

- Garnish with lemon peel

Shake with ice and strain.